Thanks to Kate Kendall for inviting me to give a talk at the inaugural IndieConf – a conference for startups doing things ‘the indie way’ (self-interested plug: my post on startups vs SMEs vs indie businesses). It was a great conference with some interesting and vastly more qualified speakers than I.

For the purpose of the talk I’ll use ‘startup’ in a very inclusive and general sense (incorporating VC funded high growth startups and indie type startups/businesses (including bootstrapped companies)).

Below is a sanitised version of the talk. I intentionally asked details I spoke about to not be Tweeted so I could tell a few stories that probably aren’t for public consumption, at least at this time. Maybe one day.

Warning upfront – bit of language in here, because that’s probably what I said at the time.

This talk is all about the hard things I’ve learned, usually in the most stupid way possible.

My name is Hugh and I run a company called Sked Social – we schedule and publish stuff to Instagram for brands from small businesses to big enterprises. This is going to be less about what we do though and more about the things I’ve done wrong.

<Request not to share info I talk about online unless it’s listed on the slides>

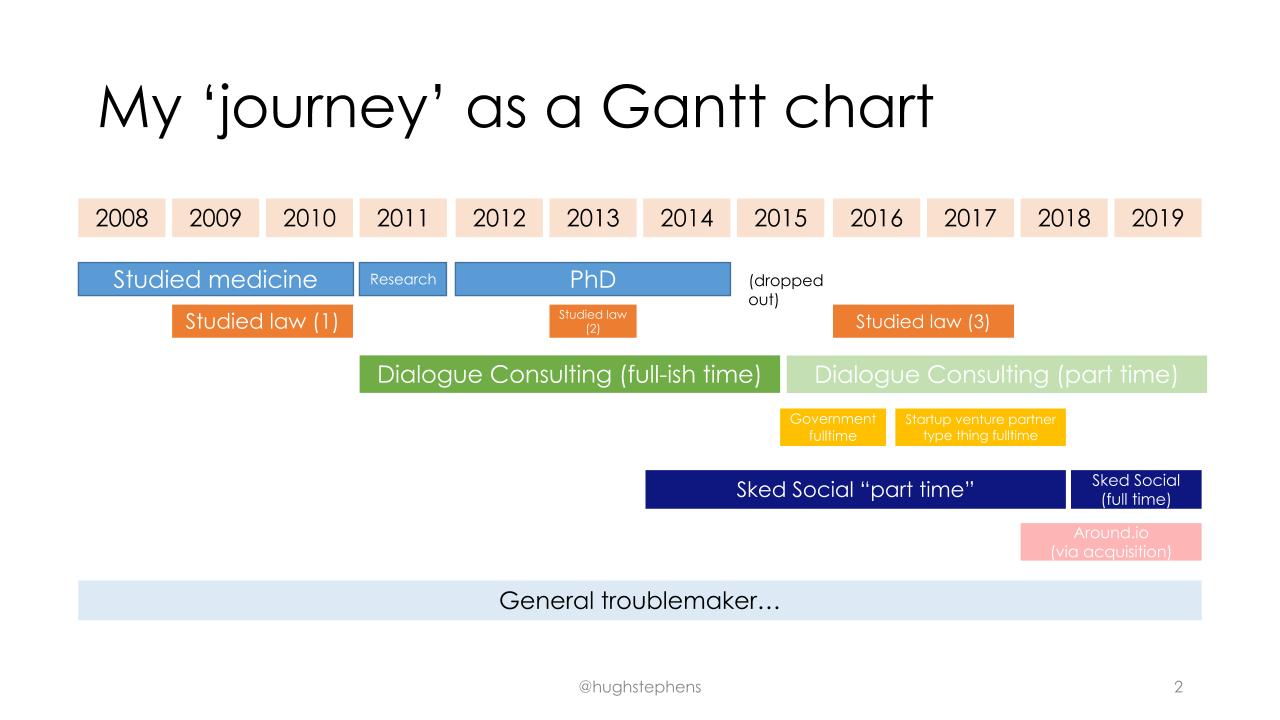

So I have a strange path to technology and startups. I started out in 2008 studying medicine at Monash Unviersity, then spent a bit of time overloading that with law because why not.

<If you already know my background skip to next slide!>

Then for various reasons, I started doing my honours research (in the middle of my undergrad, it’s weird).

I spoke at a conference about a topic I thought was interesting – how the concept of proximity in duty of care on a medicolegal level applies to mental health professionals’ use of social media – and someone asked me if I did it for work. I said yes.

Thus Dialogue Consulting was born, which took up most of my time despite me ‘doing research’. We did strategy and risk management consulting work for the usual boring client sectors – insurance, banking, government and so on.

To buy some more time, I persuaded the university to let me turn this into a PhD. Somewhere along there, I tried studying law again and then dropped out.

After a few years of not doing any PhD work, I finally dropped out from medicine and my PhD, and I believe I’m the only graduate with the alternative exit degree from medicine and the honours degree at Monash.

A client project made me realise how much time was being burned by businesses (big and small) handling Instagram content. So over a quiet December-January period, I built a totally rubbish MVP. More on that later.

So I was doing consulting full time and had this piddling little platform, but then got insanely burned out because god, services businesses are crap and so difficult to scale because it’s not funny.

So I went and worked in government to have a bit of a career break, doing some consulting along the way. Learned tons, worked with great people.

Government got boring. I didn’t really believe my “side project” tech platform (then doing pretty decent revenue, but at the time I thought it was just a little side thing) was much of a thing. So I took a job doing some work kind of like a venture partner at various VC funded startups full time (one in particular who I won’t name, but I also learned lots there about the VC path).

Then I realised I was dumb doing that. So I tapered my way out and decided to go full time on my ‘side project’, which by then had about 15 or so employees. That was only about 18 months ago, and we did a small acquisition early 2018.

We’re at about a $6m annual run rate currently, depending on how fondly the currency exchange gods look upon us. We never raised any money and have grown from customer revenue, and have been profitable since pretty much the start.

All through that time I caused all kinds of trouble.

Startups are fucking roller coasters.

Your life is about shooting between the highs and lows, and everything happening at a pace you can barely keep touch with anything.

But like a roller coaster, you learn to love it and thrive from it. It’s a weird kind of BDSM that you just can’t give up.

This is all about my roller coaster journey.

One thing my business is not is a ‘lifestyle business’.

You will see VCs and other people in the ecosystem telling you “oh, what a great lifestyle business you have there”, in this incredibly paternalistic and condescending manner.

Maybe you actually want to create a lifestyle business and that is awesome, good for you. Planned and started that way, it could be a thing, but it’ll still suck you in (at least at the start). You will inevitably get ‘the bug’, and welcome to your new life.

As previously mentioned, companies are hard, and they are shit. Indie businesses are often harder than a funded business, because you must turn something out of literally nothing, or negative nothing.

Personally, my aim is to survive.

It’s not this experience of sitting at a table smiling with hipster friends, screaming ‘BUSINESS!’ as the dollars roll in.

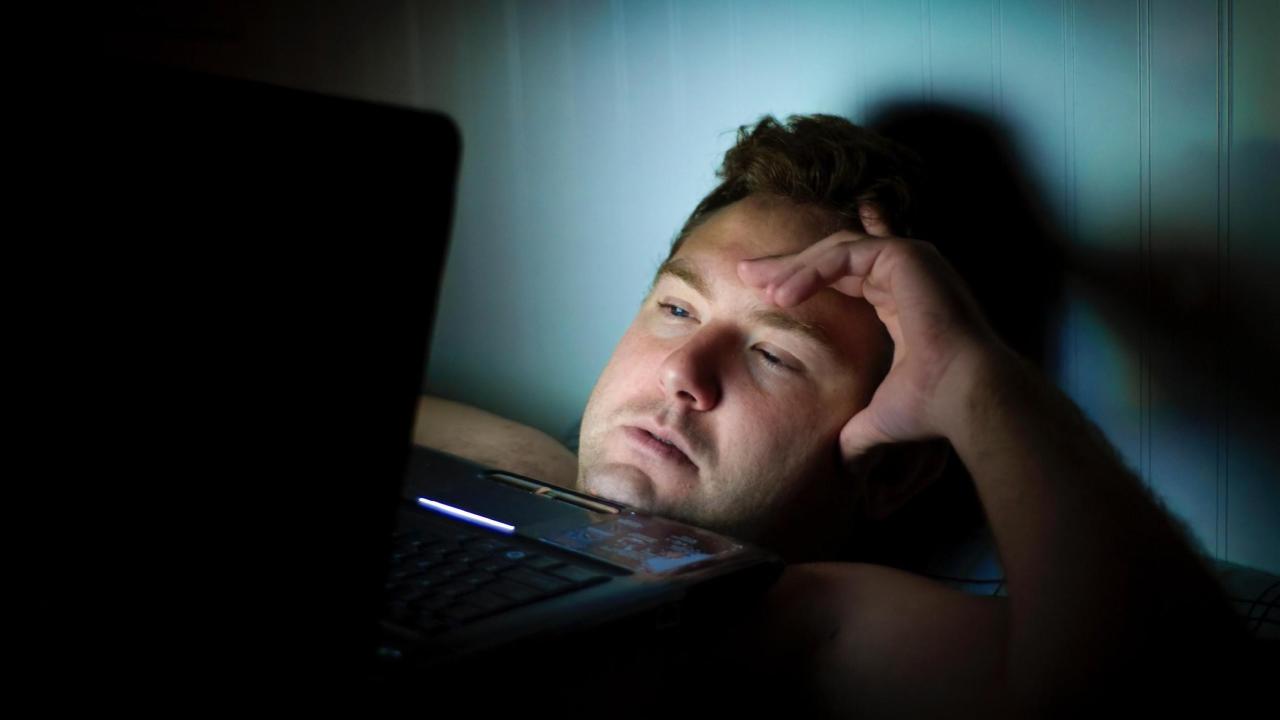

It’s this – waking up at 3am every day realising that something has gone wrong, and having to fix it [or as Scott Thomas from Creatively Squared commented to me, not sleeping because you don’t know how to fix it…]. You’re Bob the Builder, if he was on-call 24x7x365.

This is not a lifestyle business unless that lifestyle happens to be having a child that never grows up from being a young toddler, and it also happens to be a server.

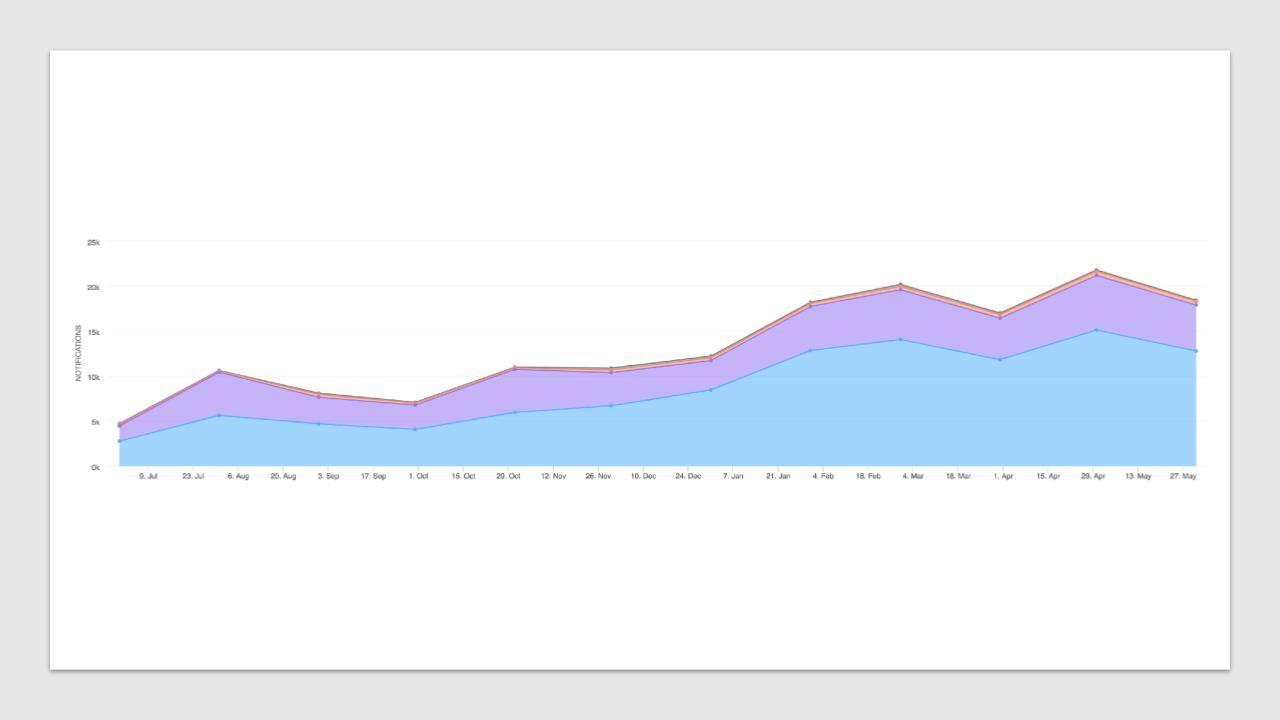

This is the number of Pagerduty notifications we send each month. Pagerduty is a tool for developers that sends you alerts (push notification to SMS to phone call with a Microsoft Sam voice) when something is not right.

We have Pagerduty piped into any problem that a post might have going to Instagram, and so for example in May we got over 20,000 notifications sent. For that month.

I actually didn’t realise how insane this chart is until I was chatting with John from Gleam over beer. His Tweet after:

John’s team is at notification number 212, while we’re at about 700,000. Luckily ours are designed to auto-resolve and things like that, but stuff still goes wrong.

The biggest downside of being a solo founder is that you’re responsible for all of this.

In the early days there isn’t anybody else, and even in the later days, you usually have your fingers in so many pies it is just easier [ed: not necessarily smarter].

Until about 2 years ago, I was on call the entire time. Thankfully now Gerold on our team looks after 9pm to 9am (my time) 7 days a week so I can sleep.

In the first few years, I’d reliably be woken up every single hour through the night when my phone started ringing.

My partner has PTSD from that noise – for him, it was certainly a rude introduction to my life when he’d also be woken up all night. See what I mean about the kid thing?

And it doesn’t just stop there. Harry (said partner) has a series of photos of “Hugh working in exotic locations because something has gone wrong”.

Here’s us in the British Virgin Islands late last year, when we managed to have a huge database kerfuffle:

I am wonderfully skilled at finding the only places that Wifi or phone reception exists in any location. Also power points in obscure places like bars on islands.

This is not a skill anyone should need to have.

I tell really early stage founders that at some point, the business will ask you to write a cheque for your soul. And the lesson as a founder is that you have to be okay signing that cheque and handing it straight over, no questions asked.

At some point, your company will try and break every relationship you hold close and dear to you.

I am forever thankful that Harry puts up with it, but we probably don’t adequately talk enough about the experience of the partner of a founder, because it’s like doing a startup without doing one.

This is even worse as a solo founder.

Anyway so in the midst of this, some people will condescendingly tell you that you’re running some small or lifestyle business (lol yeah right as if running a café is really that much easier than a VC funded startup).

They are assholes and probably haven’t done anything substantive in their lives, so they are dead to you.

The funny thing with VCs though is that it’s a game of home runs. The majority of their portfolio writes down to zero (ie, it is dead). Of course, everyone wants to be the next Facebook or Google in that portfolio, but statistically the majority die.

A lot of their time is putting sprinkle on the poop, trying to mark up the rounds until the business can somehow round the corner and ‘hit product/market fit’. Or pass it along in an acquihire to the next entity in the chain.

Your ‘indie startup’ or whatever you wish to call it, with some amount of profit and (god forbid) longevity, at least is not dead.

Growth is scary. Everything you read is about ‘holy shit look at how much we grew’, ‘that business is growing like wildfire’, growth growth growth.

I was always afraid – was I failing that month that we had negative net MRR growth? Am I a bad founder?

In reality, my experience is that bootstrapped companies can’t cover bad months by burning money on acquisition. A lot of the model of a VC funded business is to burn money on acquisition to monetise people down the track (in B2B, that’s just CAC:LTV, in B2C it might be until the network effect comes into play and you can monetise).

To be clear that is fine, but when you aren’t playing or can’t play that game, your growth is going to be more choppy.

Compounding takes time though, and the ‘long slow ramp of SaaS’ is a thing that I have certainly experienced on a deep personal level.

For those yet to start – just start today. When you don’t start, you lose time that you could otherwise be compounding learnings or growth.

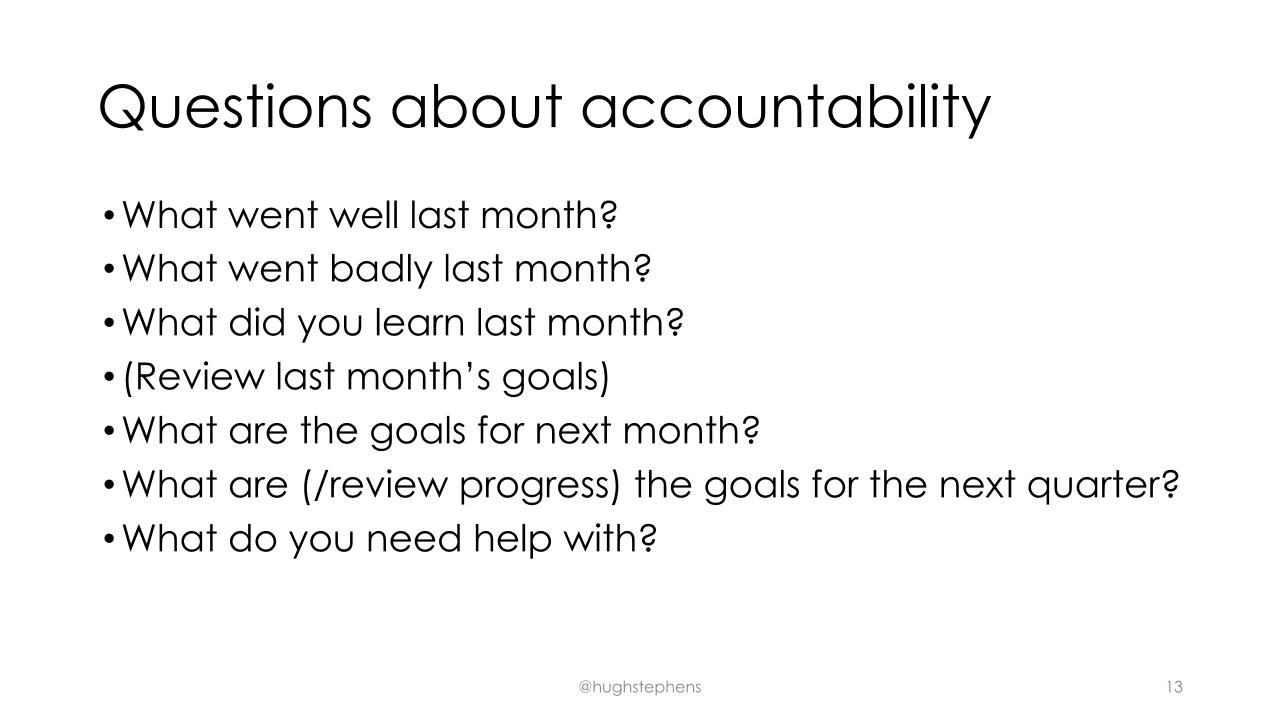

The next thing I’ve done really badly (and still do) but wish I did better was accountability. You need someone or some people to tell you when your eye is no longer on the ball.

Here are some of the questions I like to go through with people to understand where they and the business are at.

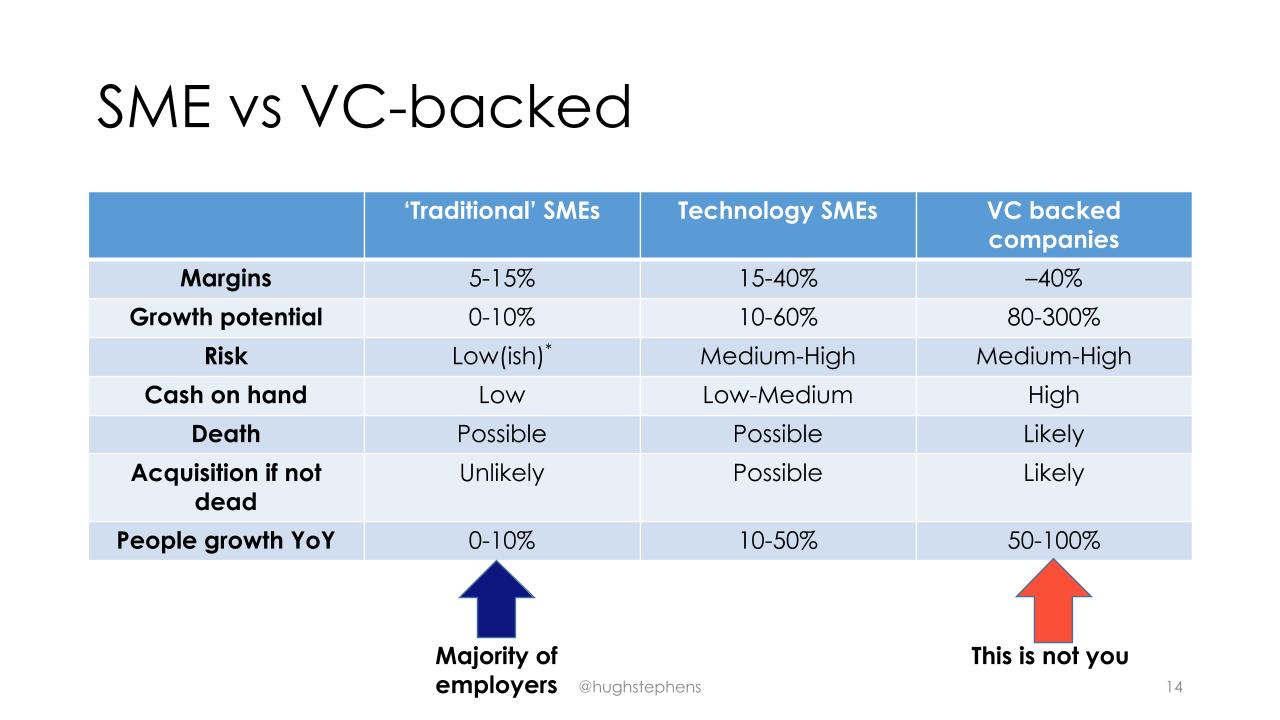

Let’s call a bootstrapped or indie technology company a ‘Tech SME’ [SME = small to medium enterprise]. You’re essentially a traditional SME like a café or manufacturer, but with better margins and growth potential. Your headcount growth will be bigger than theirs.

You take on a lot more risk though than a traditional SME, so you are trading those margins and growth for something.

You can accept markets where you don’t need to grow 200% year-on-year for 10 years (that’s actually … really hard), because you have margins. Margins give you optionality and some leeway to forgive your sins.

A typical VC backed startup will have negative margins (at least early on), huge amounts of growth potential, and grow people like crazy.

This is why the number of people you hire is not a good metric for success – if you try and keep up you will run out of money because you are not burning money like a VC backed company.

You are also less likely to have an acquisition, because often you will be a single point of failure. That is fine! At least you are not dead.

Indie companies often consider a metric of ‘revenue per employee’, which I think is a much better measure for companies like us as it tracks the semi-linear relationship between revenue growth and headcount growth.

[As a side note, there is a separate article all about VC funded vs indie companies and why I actually believe in the VC model for the right types of founders and companies! I do not think it’s some kind of evil cabal of people fucking over founders at all, despite some suggesting I do. The key is making sure that incentives are aligned and both parties understand what the goal is…]

You will have near death experiences.

A lot of them. Personally, I have about 2 a year.

They are shit and you will feel it viscerally.

You will be surprised though at how often you manage to survive.

Every 6 months or so, I’ll turn to Harry and say “Harry, this is it. We’re over, we are going to die.” He’ll patiently tell me that I said that 6 months ago, to which I’ll reply “no, but this time it’s different”, which he’ll then tell me that I said that last time too.

I’ll retract into a shell, and hugely underperform in my job as a manager and my role as a partner. It is definitely Not A Good Thing, and I do not recommend it for a nice life.

One thing that at least makes it feel a bit more amusing is a saying of an old employee of mine, who every time will tell me “Sir, this isn’t the end – it’s just the next chapter in the memoir“. I find that’s a cute way to consider it.

I find you actually learn all kinds of things through these experiences though, so don’t discount the education.

One thing I will say though – not raising money is not some kind of damn badge you get to wear being a bootstrapped or indie company.

You’re not special. Nobody cares. Good for you, you didn’t raise money, maybe you worked out a way not to need it.

Don’t go off mortgaging your house just so you can keep wearing your badge of honour and acting all holier-than-thou.

If you need to raise money, go and raise it. Otherwise, don’t.

Just make sure your business model matches the business model of the money you’re taking (VC/angel/bank loan/whatever), and what they can do to help outside just money. They usually can’t help much regardless of what they say.

You might need money later on, and that’s okay! Take it.

Work another job if you need it. Otherwise don’t. Nobody cares. Either way it’ll wreak havoc with your personal life.

It is okay to make money.

The frequency that you have to tell someone that making money is okay in today’s capitalist society is strangely high.

The secret to business is charging people money for something, and charging them more than it costs you to sell. This is not hard and it is business 101.

Venture funding has kind of distorted this for a while now, but if you go back to thinking you’re a tech SME, ask yourself if you think a café owner has any margins on the coffee you buy (…they do, or they won’t be in business long).

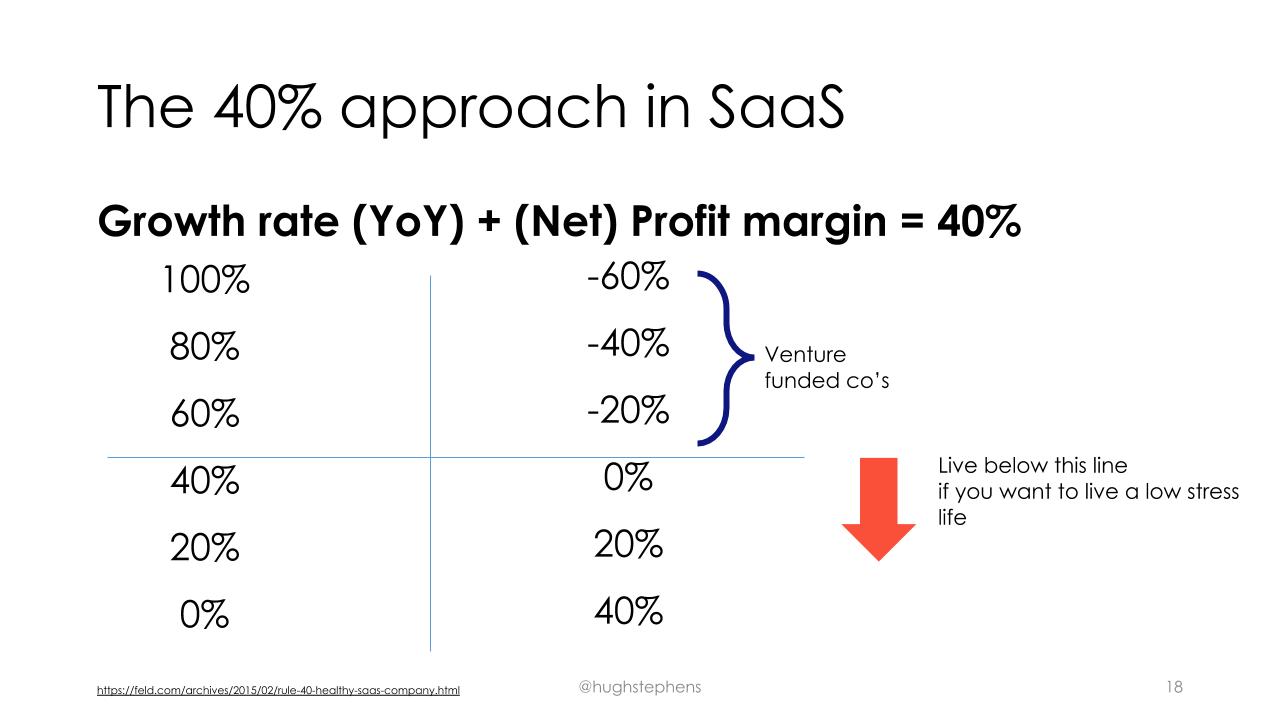

Brad Feld has a great post about his 40% rule in SaaS.

Essentially, your year-on-year growth rate plus your net profit margin should roughly equal 40%.

If you can do better, great! Good for you. But I think it’s a good thing to think about, and gives you some idea of how much you should ‘reinvest into the business’ versus take out into your own pocket.

Venture funded companies typically live above that line – they are growing like crazy but also losing tons of money, but that’s fine because it still meets the 40% rule.

The secret in non-VC-funded companies is being below that line. That is less stressful, because you have (some kind of) profit, and profit buys nice things and makes it easy to dig out of your mistakes. The worst mistake you can make is being above that line.

The thing is, indie companies generally never sell for tons and tons of money – say 3-12X EBIT. Sometimes you’re measured on revenue but usually not.

So it’s totally OK to take money out along the way to de-risk the potential of death or a pretty average exit.

This “you will not sell for that much” is doubly so when you are a single point of failure. The E-Myth is a good book that explores this test, which I fail spectacularly.

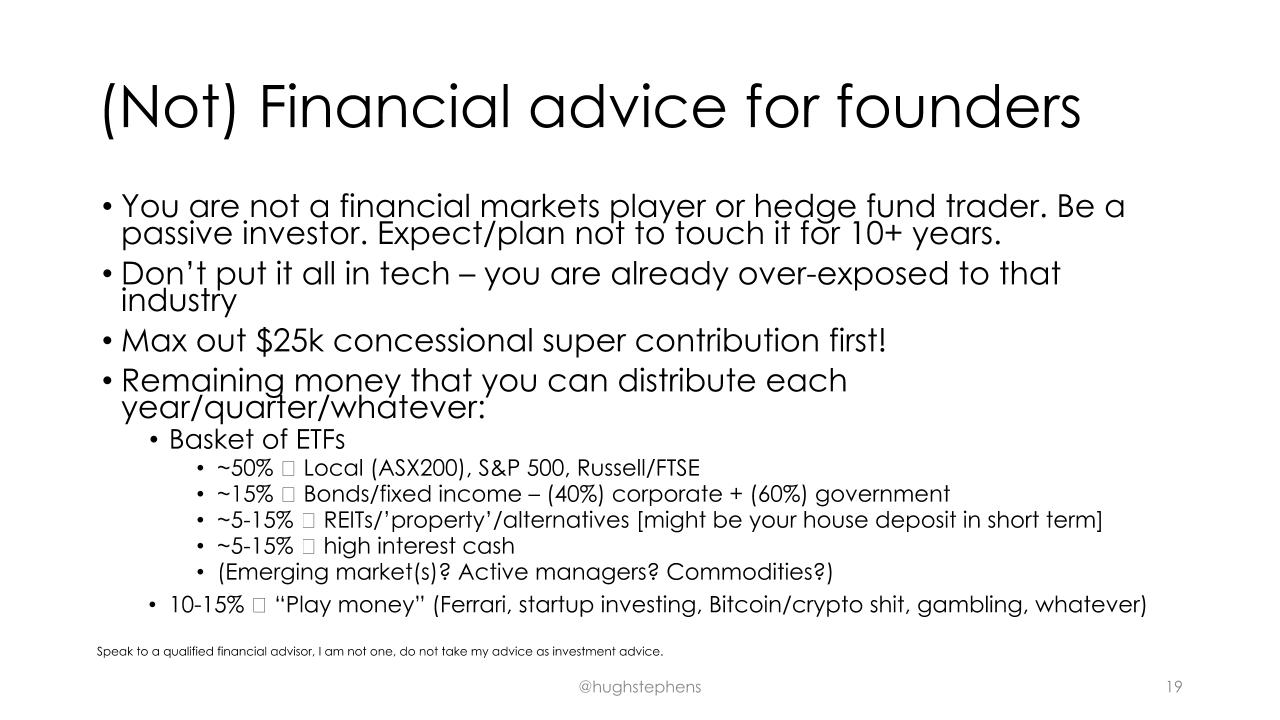

Something rarely discussed is what you do with this money though.

I am not a financial advisor and this is not financial advice, but here is my two cents anyway.

You are not a financial markets player or hedge fund trader. Do not try and become one, playing the markets yourself. Ideally, expect or plan to put it somewhere and don’t touch it for 10 years.

You are already horrendously over-exposed to tech. I get it, you understand it – but don’t put all your investments in technology, that is dumb and bad financial everything. Tesla is not a good sole investment.

Max out your concessional superannuation contribution. We’re really lucky to have superannuation in Australia, and there are all kinds of tax benefits your accountant can tell you about. I am also not an accountant.

The remainder of the money you put into a basket of ETFs. My rule of thumb is like this (see slide).

The trick is to keep some small amount – 10-15% – as play money.

With that, you can buy a Ferrari or whatever depreciating asset you want, or invest in startups, cryptoshit, go gambling, whatever. The idea is that this money lets you feel like you’ve “made it”, but you can afford to lose it all.

Watch your money and expenses. Just like VC funded companies, indie businesses can also run out of money.

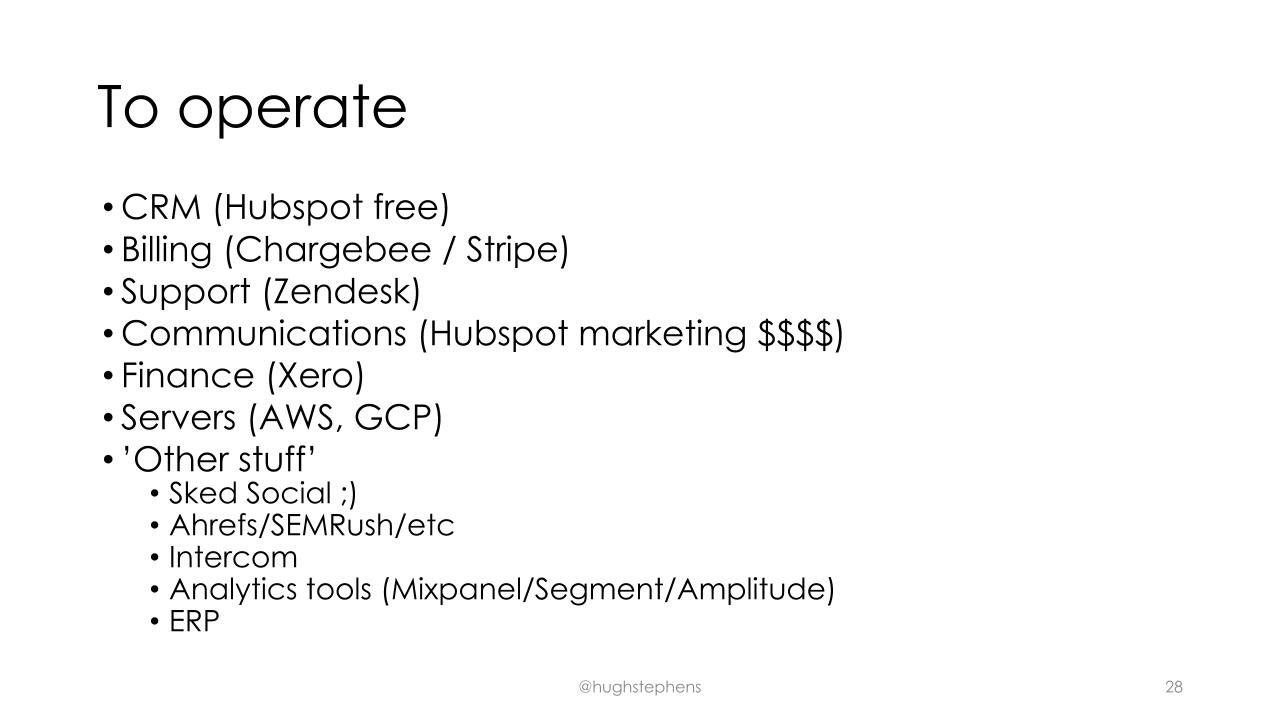

Spend creep catches up on you, and SaaS is big for a reason – our biggest cost after staff and servers is subscriptions.

I regularly cancel all of our credit cards (reporting them as lost), and you’d be astonished how many businesses come out of nowhere to complain the card isn’t working.

As a side note, if you are running a subscription business and you don’t send email receipts by default, you are an asshole. Literally nobody complains that you remind them that they’re paying you – if it’s really that much of a problem, add an unsubscribe link.

And like every business – cashflow is king. VC businesses talk all about ‘billings’ and other abstract things that are not dollars in a bank account, but you can’t pay people with billings, you pay them with money.

I have had the experience of a cashflow crunch like most business owners, and it is horrible. You will never do it again after it happens, and it’s usually the only way that you learn about cashflow.

As I mentioned earlier, running a company is lonely as shit.

Indie startups in particular are lonely as shit – you do not have a handy portfolio of other things your VC has invested into that you can comiserate with, or regular meetings with your VC who has (hopefully) actually been there before and can give you the kick you need.

It might be nice to not have a cofounder when the business is spinning off profits or when you exit, but it is crap earlier. It’s usually crap then as well.

Regardless of whether you have a cofounder or not (extra so if you are solo), your partner will take a lot of the heat.

As I mentioned, your business will ruin every relationship you hold dear.

Hopefully your other half is patient enough to ride the roller coaster with you. The bad news for them is that if you’re entrepreneurial, you’ll keep doing it anyway.

I am thankful of the times I’ve been told that things are getting too much by Harry – embarrassing as it is, without that I’d probably be burned out to a crisp. Make sure you have people around you who you trust enough to listen to advice like this.

Keep in mind though that sometimes you and your investors’ best interests may not be aligned. Understand why they are making a certain request or recommendation before you follow it blindly.

All advice comes with biases. I like to tell people to seek advice from people that can give it to be:

- stage relevant – they understand and have experienced the stage that you are currently at [not some post-IPO thing]

- time relevant – their experience was recent, and not 25 years ago when the world was totally different, and

- type relevant – they understand the type of business you are in.

On that last one – I for example can’t tell you much for B2C businesses. I don’t quite understand them that well. I can ask the questions I know to ask, but I can’t tell you what your acquisition cost should be, or tips for different channels, or how to close that one enterprise deal trying to negotiate some weird term into the contract.

That’s OK, but I know not to give that advice, or at least to make it clear that I’m limited in how I can help.

There is not a lot of good advice around for non-VC-funded technology companies. I hope this will change in the future, but there are nuances that are totally different in pretty much every business unit.

How big is big enough? When do you know you are ‘doing well’?

Lol jokes, you will always feel like you aren’t doing well and you are never big enough. I have struggled with this personally many times, and probably still do.

‘Big enough’ is a continuous moving goal – $1m ARR would be awesome! Oh no, $10m! – and so on. Most of those numbers are arbitrary bullshit anyway, and every new stage brings new problems so it doesn’t get easier.

When you feel like everything is great and the business is growing, it feels awesome. You are god.

Then one day, something changes. Maybe the competitive landscape changes, and someone muscles in on your turf. I dunno, but it always happens.

The hardest thing is the daily grind when the business is going sideways. But you have to just keep waking up, doing the deeds, going to sleep. Every day.

This is the chart of MRR from Baremetrics, which the founder Josh shares publicly and I thank him for doing so, even when things aren’t going great.

That red section is hard. You have to keep going and keep living, but your whole narrative about how growth is good is suddenly no longer valid. You might have some negative months! You will feel like shit. But it happens.

It’s really easy to get too big for your boots though. You feel like things are going well so you hire all of these people.

But then things suddenly don’t go well, or the business slows down, or you’ve forgotten about seasonality.

Hiring people is a false economy and whatever you do, do not fall into the trap of feeling that number of people = success.

Don’t fall into the classic trap of hiring a sales team because you think you need one (lol they NEVER sell as well as a founder, at least at the start) or because ‘you are not good at sales’. It is time to learn.

Plus anyway – not all companies need a sales team. Big businesses are progressively learning to buy stuff without dealing with a sales team, and it can be refreshing when they talk to someone with deep operational product knowledge than a salesperson.

It’s better in so many ways to build for efficiency rather than people, with the caveat that you shouldn’t let tech people go crazy.

Someone asked on Twitter about what ‘stack’ we use of tools. Here’s my quick summary of what we use (in parentheses) and some of the other areas you might want to think about. [Ask me on Twitter if you have questions about this I guess].

Like literally every other business, the hardest thing is people. The second hardest is people, then the third is people.

It is really hard to get right. In VC businesses, the saying is that you hire the person for a role that will suit them 12 months in the future – you’re always hiring for the next step.

In indie businesses, you’re usually under-resourced so you’re hiring for what you needed 6 months ago. This can result in all kinds of traps. In particular, you aren’t hiring insanely quickly, so you can’t make up that one crap hire in volume later.

Mistakes I’ve made hiring are innumerous and there is not enough time in the day for me to describe them all.

My short thoughts are that crap hires come in all kinds of flavours. You can be too small for a hire and not ‘grow into them’ (the classic is the Google-scale engineer wanting to do Googly things for your tiny startup, it does not work).

I have two final things to cover that I just keep telling people so had to mention it.

If you are a tech company, have that in house. Do not outsource technology to some dumb agency.

I never studied software engineering, but I taught myself enough to be dangerous and to do the basics. This is not THAT difficult, and while at a later stage you shouldn’t be doing engineering work if you aren’t an engineer, you have to start to get the compounding effect.

I call bullshit on people who say otherwise. Sorry not sorry.

Do outsource non-core things! Don’t build your own billing stack just for funsies. Or make a custom programming language. That is dumb, do not do dumb things, even if engineers think they might be fun.

Finally, the best advice you’ll ever get about hiring is that when there is doubt, there is no doubt.

I’ve worked in bigger businesses like government where you have a “performance management” process to improve poor performers.

You are a small business, not a government department with thousands of employees. You do not have a HR team who can do performance management shit. If someone is not performing, fire them. You can still do it nicely with severance etc. [Note: I am not an employment law specialist and do not take this as employment law advice – you still have to comply with the law].

Everyone will tell you that you will always fire people too slowly. It is incredibly hard, and those conversations are hard to have – you will always remember the first person you fire, the first time you have tears, and so on. But that is your job.

Hire slow, fire fast.

Finally, here are my biggest mistakes.

I didn’t treat the business like I should have. I should have moved to full time earlier. It was a dumb mistake and I thought I was being smart by overloading myself, delivering poorly at everything I was doing without actually needing to (I didn’t need to work to pay the bills, the business could have).

I didn’t take it seriously enough, when in reality I was asking people to do exactly that when they came to work for me. That wasn’t fair or right.

I hired ‘B players’ – the people who aren’t quite right but they are OK – because I needed someone now. That and generally making bad hiring choices.

I still don’t deliver enough accountability to my team. It’s hard to do well, and I am still learning that.

I don’t have enough accountability personally – that is both good for my mental health and bad for my business.

And I have never fired people fast enough.

In summary, this is what we covered.

Happy to take questions! You’re welcome to Tweet me (my DMs are open and it’s warm, jump on in!) or drop me an email.